There are certain artists with whom you dream of coming into orbit, and Wadada Leo Smith is finally in our galaxy. Clara and I went to see his trio play Constellation a while back, when the Cubs were winning at sportsball or whatever – so it was a small house – and both of us were struck by the patience and nuance with which he infused his performance. Every note felt purposeful and considered, and more importantly, honest.

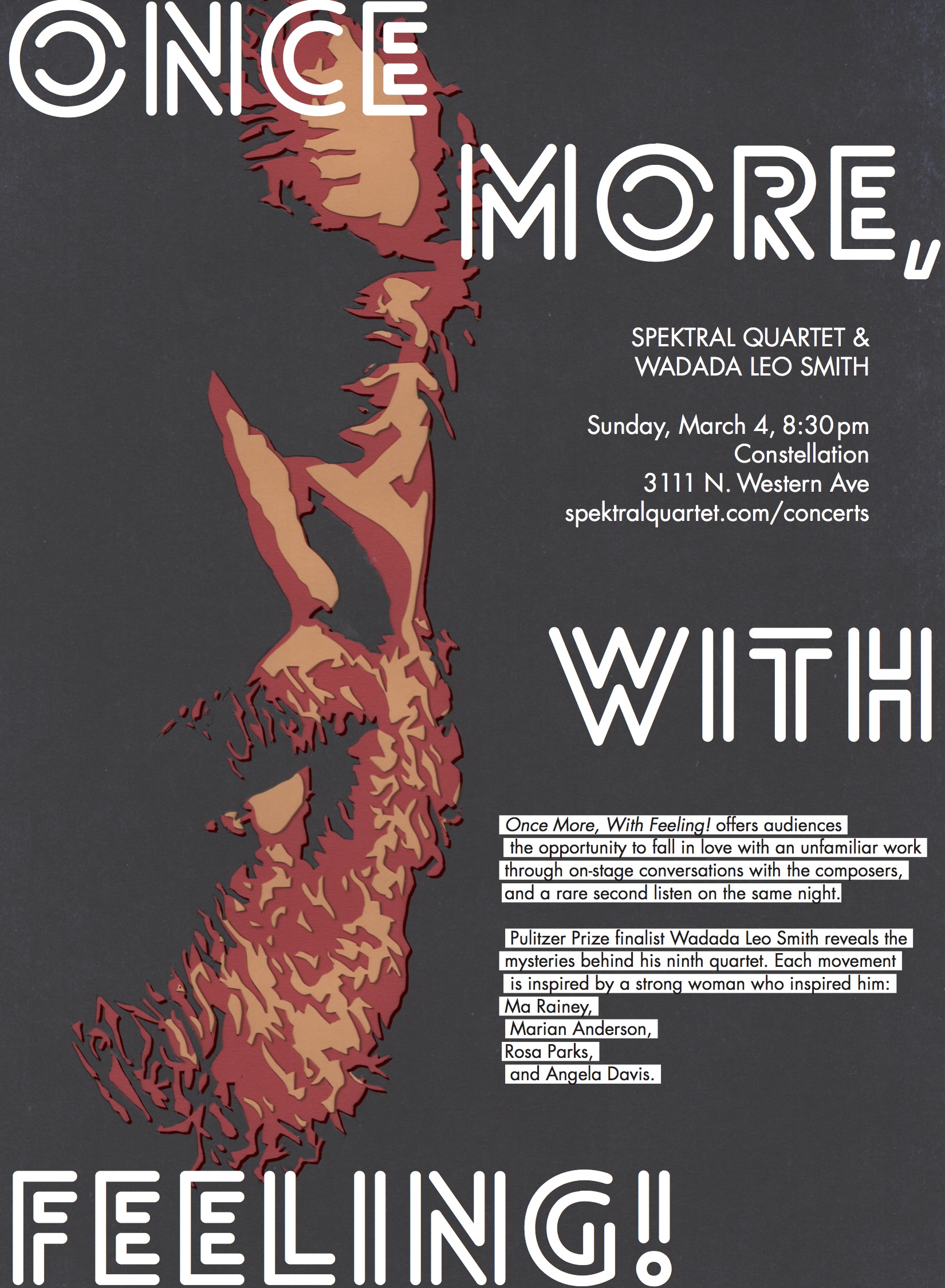

We feel very fortunate that he was willing to fly out for our upcoming Once More, With Feeling! series this Sunday (3/4), and we know that if you stop by, you'll leave with a changed and inspired brain to tackle your own creative projects – to dig in and uncover what it is you have to express.

Our correspondence with Wadada has been voluminous, so we thought we'd take a step back and ask him about his musical journey more globally...to help get our – and your – head in the game for what is likely to be a singular night of creativity and music-making.

Doyle Armbrust: Can you take us back to the origins of your life as a composer?

Wadada Leo Smith: I began to compose at the age of twelve. My first composition was a work for three trumpets. When I felt the need to compose music I did not ask anyone to teach me or show me how to make a composition.

I started with the "notes" that I knew and went from those "notes" to other "notes" to make my composition. After completing the score I asked two friends who also played the trumpet to play the music that I had composed. I learned from hearing that music within days after composing the music. From that moment to today I have never asked anyone, teachers or musician friends that I know, to show me what to do in a composition.

After composing my first piece of music, I went to my school's library to research what a composer did, and to look for information on other composers. After that I realized that I was a composer.....that wrote scored composition, and that composing was what I did. Over the years and with hundreds of compositions I continue to work on using my inspiration, skills, research and dream state to make the best art that I can. Soon I will have twelve string quartets. When my eleventh, (a set of six quartets) is finished, hopefully by the end of September, I will finish that quartet.

DA: Even though you were self-taught, you must have had influences, right?

WLS: Yes. I started composing string music in 1964 after hearing string quartets by John Lewis and Ornette Coleman. Charles Ives and Bela Bartok and Debussy's music also played a part in my research of quartet music. And although these composers came later, after I had already started to write for the string quartet they all had an impact.

I saw in Debussy's works a larger possibility for creativity then I did in the music of Arnold Schoenberg and the Austrian school of composition. Coleman's music had the greatest influence, because his music and string quartet writing offering a fresh vision of how to employ freedom and creativity with the force inspiration to create a work of art – an idea that seem far from the formalized way that composers of Europe and the concert music schools of composition in the United States.

Lewis's string quartet music reflected a very good example of those schools of thought, and was clear enough to show me that I did not want to compose in that way. Ives's works suffered from him not hearing much of his music in performance; and his uses of "folk music" sources was also something I was not interested in doing. A lot of his works look at the same issues and often would have the same "tunes" imbedded in his works. And yet there are major master works coming from him: the fourth symphony, the piano sonatas, and Three Places in New England are some of my favorite music.

DA: What inspired you to write for string quartet, specifically?

WLS: My vision of music creation is in the string quartets. I understand something about the history, and the beginning of European music and string quartet writing. But what interests me about this history is that I can take those instruments out of their historical context, and recondition those instruments in a different world view, with a different meaning through my use of making art. And, because I came up in rural, segregated Mississippi, I don't need to prove anything to myself or others about composing. Therefore being mostly isolated in my development as an artist, it allowed me to be opened enough to consider any idea – a dream state where I am able to pursue any research that I feel is necessary to make sense to me in my art.

DA: So within this somewhat historically-codified realm of the string quartet, where does that freedom reveal itself?

WLS: A majority of my string quartets have some language of the creative elements, Ankhrasmation, and a look at the ensemble form and what that investigation means – the collective ideas as to how to put the music together as a unit. Even in cases where there are clearly written lines, the artists in my RedCoral Quartet use their imagination to construct or shape the music lines, and therefore it's flow.

My scores are essentially non-metric, and a full page is a "bar" with no down and up beats.

Part of the horizontal flow of the music comes from the score but within ensemble the leadership shifts from person to person as the decisions for continuity keep changing from page to page.

DA: One of the elements that drew us to your ninth quartet is that it is inspired by four important women in history.

WLS: My String Quartet No. 9 is tribute to four women: Ma Rainey, Rosa Parks, Marian Anderson and Angela Davis, all of whom have had a profound effect on the arts, and who provided social commentary. They were activists concerned with the ideas of liberty and freedom for all people in America and around the world.